The Legend of Satsue Mito

Posted by Yoshi Kai on 10th Mar 2016

April 7 marks the 102nd birthday of Satsue Mito (April 21, 1914 – April 7, 2012).

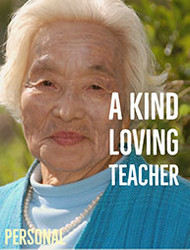

I had the good fortune of meeting Mito-sensei, as everybody lovingly called her, in 2007. She was a tender woman, and one of the most prominent primatologists the world has ever known.

I took a group visiting Japan to her house, a short walking distance away from Kōjima island in southern Miyazaki. She gave us a tour of the island and her workshop, chock-full of books and a station where she administered urgent care to monkeys in need of medical attention. It was there that she told me about her incredible life story.

Mito-sensei was born in Hiroshima in 1914. She married in 1934 and moved to Korea where she had three daughters. Her husband died of a sudden illness in 1940. World War II was raging at the time, and life was not easy. At 26 years of age, she took her daughters and went to Dalian, China, where she found work as a school teacher.

The war ended in 1945 and Dalian was occupied by the Russians. Barely surviving and longing for home, Mito-sensei took her daughters and moved back to Hiroshima in 1947. And then things went from bad to worse.

1947 Hiroshima was nothing like she remembered. The nuclear attack had obliterated the city, and there were widespread famine and misery.

Mito-sensei packed her meager belongings, took hare daughters and left Hiroshima for the relative safety of south Kyushu, where she got a little place next to the tiny Kōjima island.

Kōjima, since anybody could remember, had been populated by a species of monkeys called Nihon-zaru (Japanese macaque). During the war, most of the monkey population was wiped out by people hunting for food. The few remaining ones looked miserable. They were in poor health and imminent danger of extinction.

The sight of the desperate monkeys was too much for Mito-sensei to bear. She began to care for them, shared with them what little food she had, and nursed the sick ones back to health in her home.

Little by little, things got better, and the monkey population bounced back. By 2007, there were about 400 monkeys, the maximum the island’s ecology would naturally sustain, she told me. And she knew them all by the names she had given them!

Mito-sensei dedicated the rest of her life to her (as she called them) monkeys. Her research and publications have made enormous contributions to the science of primatology. She has published several books and closely cooperated with the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University.

We miss Mito-sensei; so do the grateful primates of Kōjima, I’m sure.